“[Y]ou have this tremendous advantage of reading something for the first time, which is an experience you never have again with the story. I mean, the first time is something which you cannot ever guess about, you know? That’s the first time. Then you have a reaction to it, and subsequent readings, you know, are more analytical. But, you have to start with a kind of, you know, like falling in love reaction with the material. So then it just becomes, you know, a matter of…almost like a codebreaking, of breaking the thing down into a structure that seems to be still truthful, not losing the, you know, the ideas, or the content, or the feeling of the book. And try to get it into the much more limited time frame of the movie. And the criteria is always is it truthful and is it interesting?”

~Stanley Kubrick, being interviewed by Tim Cahill in 1987

“I always thought that the real difference between my take on it, and Stanley Kubrick’s take on it was this: in my novel the hotel burns…in Kubrick’s movie the hotel freezes. It’s the difference between warmth and cold.“

~Stephen King

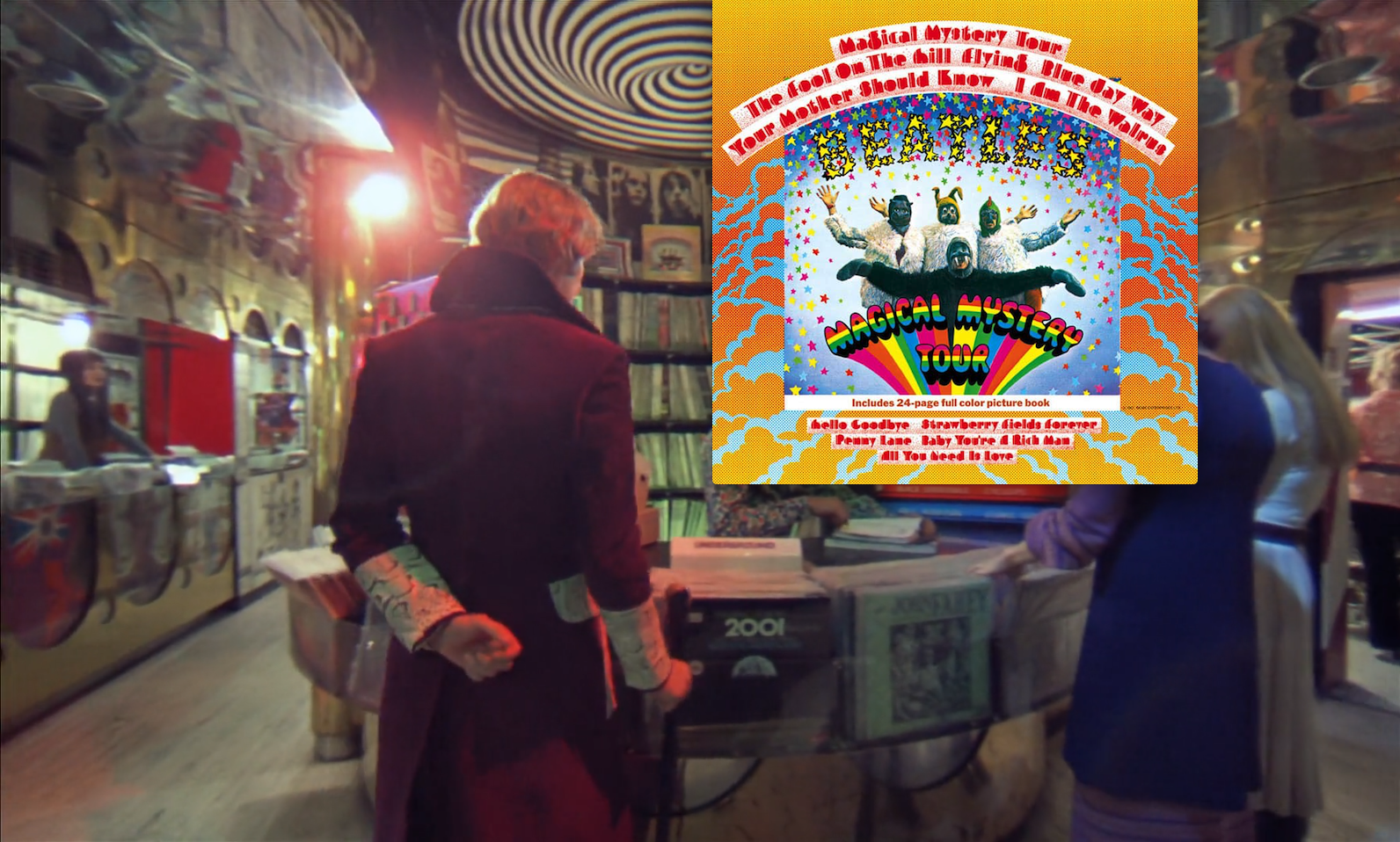

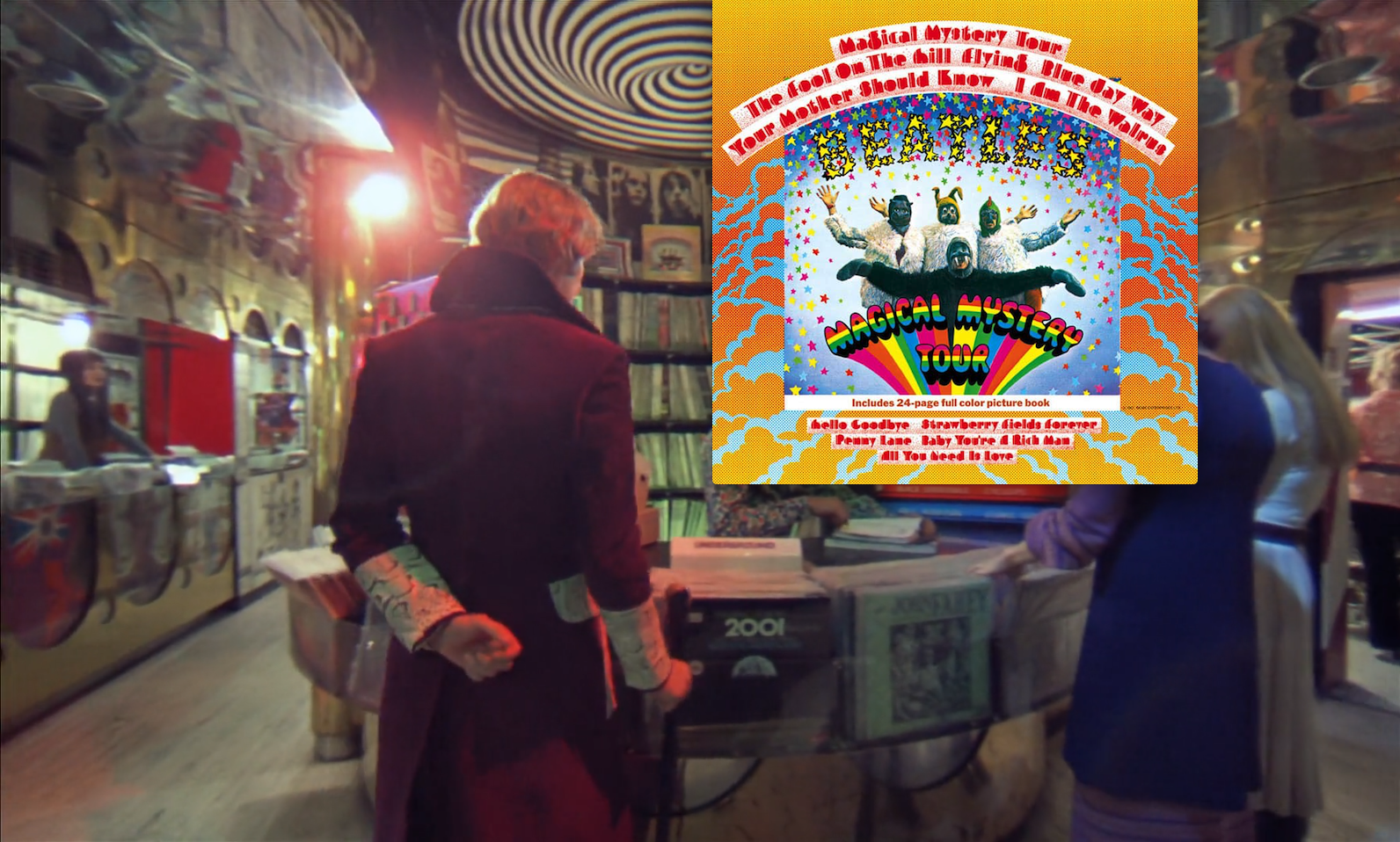

One thing I put off for way too long was to go through King’s novel again and look for where Kubrick might’ve derived his inspirations for all these intricate patterns we now understand to lace the film. As I said in this website’s intro, it was noticing the Abbey Road Tour that lured me into these past 2 years of analysis, but my faith in that was supported entirely, and very comfortably, by the fact that King references John Lennon in his dedication to his son, and in the fact that Wikipedia had King admitting the connection. I had no idea that the ghost band at the ghost ball actually play Ticket to Ride off the 1965 album Help! (pg. 352) Or that Danny is thereafter described as Jack’s “ticket” (pg. 380) for gaining access to the hotel’s private eternity (or that the word “help” begins to appear quite a bit thereafter).

Now, I don’t know if there’s a direct (or indirect) reference for absolutely everything Kubrick included (certainly most of the artists and writers Kubrick chose to include is his orgy of evidence moments are not named in the book), but I would say that if we were to yank both these plants out of the earth, their root structures would look similar enough to cause us to think they were the same species without having to eyeball the blossom.

I was being asked a lot by curious individuals who’ve been discovering the site (and my documentaries) what I thought the deeper meaning was behind Kubrick going to all this trouble. My initial response was (and still is, to some extent): you need more? This isn’t deep enough for you?

But I can sort of sympathize.

Before discovering the almost clinical cleanliness of the Treachery of Images subtext, I was afraid that I would one day discover some secret, verifiable message in the film like, “THE BEATLES SUCK” or “FDR: NOT MY PRESIDENT” or “FREEMASONS RULE THE COUNTRY” and then have to spend the rest of my life pretending I’d never noticed it, just as not to look like some of the truly gonzo analysts that I now know are out there. But, as my findings took me deeper and deeper into Kubrick’s arch weave, my fear began to feel silly: why would he mar his (as far as I can see) peerless masterpiece of intricacy by throwing in some sophomoric sociopolitical blather?

But also, The Shining is the only novel my dyslexic eyes and brain had ever read twice (now four times), so each time I discovered another of Kubrick’s larger techniques, a ghostly sense of familiarity came with it. I trusted that feeling to mean there was some antecedent in King’s novel. I didn’t suppose King (of whom I’ve been a lifelong superfan) was the sort of writer to have the patience to work out anything half so dense as, say, what Mike Noonan discovers in Bag of Bones (1998) (you can spoil the surprise by following that link–or you can go read it yourself!). And while some of what I have to report may shock you (for what it says about the fleet-fingered King’s attention to craft), the vast majority of this analysis is simply to show that Kubrick’s inventions don’t simply spring out of holes in the ground, but come from trying to do what I now tell those readers seeking deeper meanings.

What was Kubrick’s deeper “message”? He wanted to make the best damn adaptation of King’s book that anyone could ever do. Did he twist certain of King’s symbols to suit his own purposes? Of course. But if you want to understand where it all comes from, this one’s for you.

Also, as for the spirit of this analysis: I’m not saying with utter gravity that everything I’m pointing out below is something Kubrick definitely noticed, and definitely considered when he included his own variant or reference. I’m just saying, as his super-powered laser beam brain was doing the work of “codebreaking” (his word) King’s novel, these would seem to be the sorts of things that might’ve informed his process. We should not rule out the possibility, however, that King drew these codes to Kubrick’s attention, however opposite that may run to their official statements on the matter.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- King’s Labyrinth

- The 217 Jumble Phenomenon

- Fibonacci

- Escaping Through the Nyet

- Jack’s (Broken) Ladder

- A Chain of Cheneys

- Evolution of a Masquerade

- The Story Code Phenomenon

- I’m Ready for My Slow Zoom, Mr. Kubrick

- The Mirrorform

- Other Notes of Eye Screamery

- The Shining: A Page-By-Page Analysis

SPECIAL: KING’S LABYRINTH

Okay, so I did the page-by-page analysis. I wrote out all the significant things in the book that tie to the film. But what I started to discover is that, it’s not simply things like Jack Torrance quoting Julius Caesar on page 48, and Kubrick having Caesar’s biography appear in Boulder. King has used many of the same kinds of large-scale techniques as Kubrick: the Fibonacci sequence, the lessons and escapes, significant details/sequences being significant lengths of time (or pages, in this case) apart, buried art references, and so on.

This necessitates an extremely fractured series of clues, all zig-zagging through the novel’s narrative in ways that could be quite boring (forbiddingly boring) for you to have to wade through chronologically (though, if that sounds like fun to you, I’ve left up my notes). It occurred to me that expecting you to do that would be like if I’m tried to convey what a zoo’s-worth of animals look like to someone who’s never seen any of those animals, by showing one aspect of each animal (a claw, a tail, an eyebrow), before moving on to the next detail for each animal (a mouth, a knee, a rump), and expecting them to always remember which goes with which. If you could even remember all the pieces, you’d probably draw something like Dante’s rendition of Geryon, all random parts jammed in an anatomical nightmare.

For those disinterested in such a confusion of significances, let’s look at the larger patterns I noticed in a more isolated and comprehensive fashion.

THE 217 JUMBLE PHENOMENON

The book is loaded with characters saying and thinking numbers. Sometimes there’s so many that you think they can’t possibly all mean something, and there’s a good chance some of them do mean exactly bupkis. But frequently enough, when you go the page number that corresponds to the thought or spoken number, you find a scene that mirrors the scene you were on. Or someone on the other page is saying the number of the page you came from. Stuff like that.

But my favourite example is in what I’ll call the 217 jumble. If you’re not familiar with my work on the number 237 as it appears in the film, there’s an almost nauseating amount of objects and time codes and secret photos and passages in the film that feature the number 237 coded into them. But not just 237. There’s also 23s and 37s and 732s, and so on. When Jack first walks over the spot where he’ll later kill Hallorann, the time code is 3:27, and just up the hall from him is a wall rug that features 2 vertical half-diamonds, 3 horizontal half-diamonds, and 7 interior full diamonds. Once you realize how truly ubiquitous 237s are in the film, it starts to make going into room 237 seem almost redundant (or like heading into the eye of the maelstrom).

So, where did Kubrick get the idea to do that?

Turns out, in “Chapter 25: Inside 217” novel Danny enters room 217…on page 217 (technically he’s standing at the entrance on page 216, and “stepped further in” mere words before the page turn). In the film, the first second of time code in the room is 71:50, which is like the “REDRUM” version of 217. But as Jack moves through the room, a lot of other jumbles go by (72:01, 72:03, 72:10, 72:21, 72:23) often marking the appearances (and disappearances) of the various artworks in the room (the lesson key appears at 72:11 and disappears by 72:23), until he stops outside the bathroom door at 72:31, which is like a jumble of both room numbers.

But like movie Danny, book Danny passed the room once before, in “Chapter 19: Outside 217”. Unlike movie Danny he’s not riding a tricycle, but simply standing outside the door having all kinds of thoughts about what could be inside this room Mr. Hallorann warned him so sternly about (pg. 87). This starts on page 167, and by page 171 he finally takes the passkey out of the lock, and resolves to leave nasty ol’ room 217 behind. But then something makes him stop and linger: a fire hose, “folded back a dozen times back on itself” (and doesn’t that sound like the Twice-Folded Shining, or even the Seven-Times-Folded Shining?) slips off its hook somehow and vexes the lonesome boy, as though it were a poisonous snake. It makes him think (on page 172 now) of “one of his favourite TV shows” since the word EMERGENCY appears on the protective glass. And doesn’t film Danny have a lunchbox featuring the 1972 series (at 12:17 into the film no less)?

1972. 172.

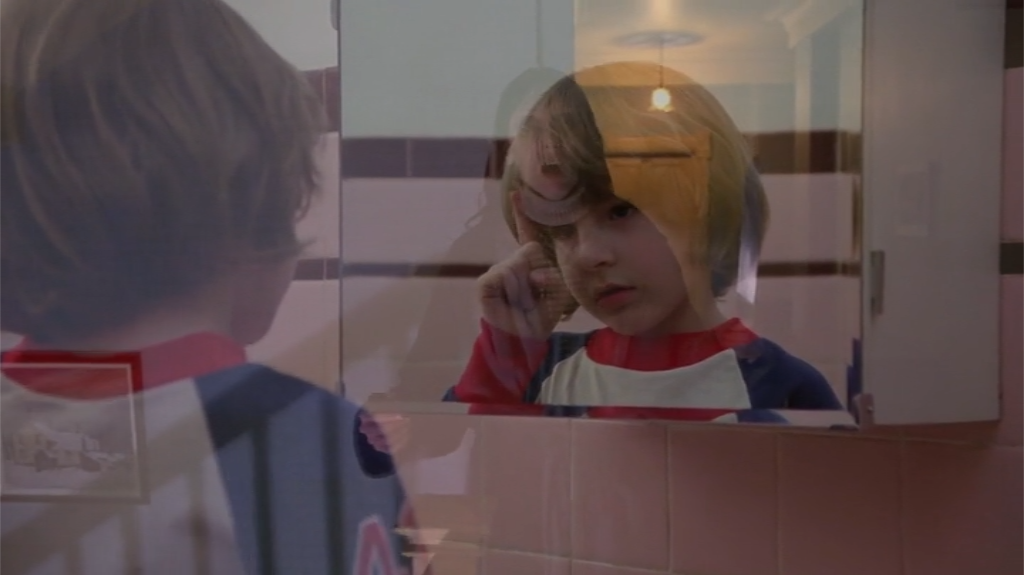

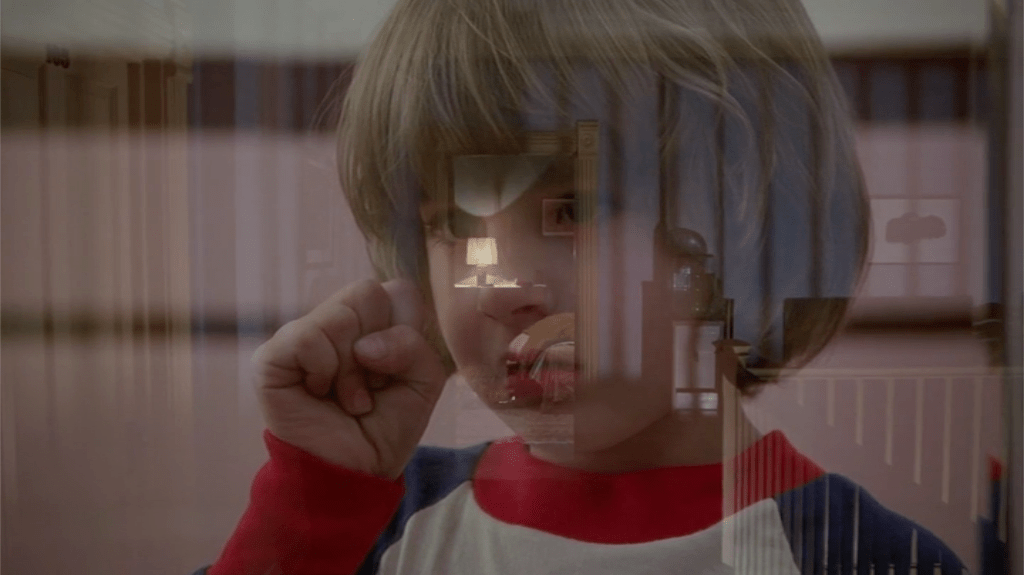

On page 127 (of “Chapter 16: Danny”) Wendy and Jack have just kicked the door down to Danny’s private bathroom, after the boy was unresponsive inside. They find him spaced out, staring in the mirror, thanks to Tony, as he explains, who appeared to him “way down in the mirror”. A locked door, a hypnotic mirror. And Kubrick’s version of that scene shows Danny’s vision and occurs in Boulder, ending at 12:07.

And while Jack’s journey through the room (in “Chapter 30: 217 Revisited”) starts on page 251 and ends on page 255, in “Chapter 32: The Bedroom” there’s a page break on page 270 as Jack descends down into sleep after the 217 episode, only to awaken a moment later within the 217 bathroom. At the top of page 271 he flings the tub’s curtain back to reveal “naked, lolling almost weightless in the water, was George Hatfield, a knife stuck in his chest.” Hatfield is the student Jack pummelled after the boy cut holes in Jack’s beetle’s tires (or as Danny likes to say, “the bug’s tires” (pg. 13)), losing him his job, and sealing his fate as an employee of the Overlook. Let me say here that I don’t yet have a “Hatfield” reference in the film, but from 27:01-27:10 Hallorann is curving toward the storeroom with Wendy and Danny while Wendy’s quizzing him on how he knew Doc was “Doc”, and as that happens there’s two postcards of Niagara Falls that appear behind Dick, on the wall of his office. If “George Hatfield” is a reference to the “Hatfield-McCoy feud” that’s one of the most famous incidences in history of two families feuding across the generations for increasingly obscure reasons, separated by a river. And the Niagara river (which is part of the Great Lakes) is part of perhaps one of the largest bodies of water that separate two (otherwise closely adjoined) countries. And Kubrick even added details about the feuding between Canada and the States, as seen in the Panet-Berczy painting of the Battle of Sisters Creek. Not to mention several other paintings depicting spots along the St. Lawrence Seaway, including one with a particular connection to Hallorann, who might just be the Hatfield stand-in.

Going back to page 271, dream Jack escapes Hatfield (with the knife “equidistantly placed between nipples”) and room 217 only to dream-shift into the Overlook basement, where he finds his “campchair, stark and geometrical”. This is where (in reality) he’ll attempt to find the Overlook’s true history (pg. 214, 224), but only manages to pull out the same wasp’s nest that resurrected into ghostly life on page 131 (four pages after 127). The wasp’s nest with its hexagonal holes, like the “white hexagonal tiles” on the floor in room 217’s bathroom (pg. 217). And doesn’t the number 237 correspond to the hotel wanting Jack to kill Hallorann? And isn’t part of that pattern the painting Trapper’s Camp?

Camp chair. Trapper’s Camp.

So where did Kubrick get 237 from? That’s a question with a dozen answers, it seems. But it’s worth noting that page 237 features Jack entering the room where he’ll have his first conversation with Lloyd, and drink his first ghost drinks, crossing (one of) the (many) rubicon(s) that seal(s) his fate.

Page 273 is the end of his 217 nightmare, in which, thinking he’s killing George Hatfield, he realizes too late that it’s actually Danny he’s bludgeoning to death with his father Mark’s cane (and isn’t it a painting by Paul Kane that movie Jack passes on his way to the ghost ball?). For more on Mark’s cane, check out pg. 223.

On page 327 an increasingly demented Jack realizes that the hotel’s boiler is in the danger zone. Watson warned him in Chapter 3 (pg. 20) that it used to be rated to 250 pounds of pressure per square inch, but he wouldn’t want to be anywhere near it at 180 after all its years of wear and tear. Here, on page 327, it’s at 212 ppsi., and creeping higher by the moment. Hypnotized by the life-and-death scenario Jack imagines the thing blowing up and “[destroying] the secrets, [burning] the clues,” and how “it’s a mystery no living hand will ever solve.” He’s referring to the hotel’s history, which has been driving him mad. In imagining Wendy and Danny getting his life insurance, he thinks, “Seven-come-eleven die the secret death and win a hundred dollars.” Talking with imaginary Lloyd on page 239 he says, “There isn’t a Seven-Eleven around here, would you believe it? And I thought they had Seven-Elevens on the fucking moon.”

On page 19 of Chapter 3, Watson says, “I tell you, this whole place is gonna go sky-high someday, and I just hope that fat fuck’s here to ride the rocket.” Then, on page 20, “If you forget, it’ll just creep and creep and like as not you an your fambly’ll wake up on the fuckin moon.” Jack relives Watson’s words from 19 and 20 halfway down page 69.

Page 19. Page 69.

And when did homo sapiens first set foot on the moon?

So perhaps this is why Kubrick associated room 217/237 to the moon. But we’re not quite done with page 327. On the next page the boiler creeps to 215, and the next we hear about it is on the following page, when it’s reached 220, which is when Jack successfully dumps the boiler (page 214–218 is Danny’s 217 escapade, drawing a link between the need to blow of steam, and Danny’s need to sate his curiosity–page 220 is the announcement of the start of “Part Four: Snowbound”). But between this 215 and 220, as the boiler passes its own 217, Jack enters a daydream about a time when his father knocked a wasp’s nest out of a tree after blasting it with smoke from a fire all day. “Fire will kill anything.” Mark Torrance informs his son. And isn’t it inside room 237 that Jack passes a painting with a Promethean connection?

Finally, on page 372, as Wendy and Danny drag Jack to lock him away (another rubicon crossed–mother and son betraying father), Jack mumbles to himself in a daze, “You gotta use smoke,” and “Now run and get me that gascan.”

Now, are there other links in these chains, or other jumbles I haven’t noticed? I would dare to say it’s very likely, but I’m not going to expend the brain power to find them. This is good enough for me.

If this isn’t good enough for you, well, then you might not find much of what follows terribly persuasive, I’m sorry to say, but I would encourage you to reread the novel yourself, if only to realize what I can’t show you in my own words: that these 217 and 237 jumbles both contain the moments I’ve detailed, and do so in relative isolation.

And that’s the key. While King is pounding us with his few hundred repeating thoughts and phrases, our job is to understand that when these pivotal things happen, he lets them sit out in the open, expecting us to be too punch-drunk to catch on. Too lost in the orgy of evidence.

FIBONACCI

The novel opens with a quotation from the painter Francisco Goya: “The sleep of reason breeds monsters.” This is actually a different translation of the 43rd piece in a series of 80, named The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. And though no one online that I can see is talking about this, it appears to have been composed according to the Fibonacci sequence. As you can see below, it might even be a phi grid. You’ll also note that the proportions are off, such that the spiral doesn’t fit perfectly across the entire image, and I suspect that’s by design. The piece is, after all, about how “reason”, which can be thought of as “logic” or even “truth”, is under attack by the fantasy of the sleeper’s dreams manifesting around her.

Then, on page 141–143, Danny is asked by a doctor to see if he can call upon Tony, and thus Danny enters a dream state where he sees “that which will be forgotten” (the hotel boiler) before seeing his father in the same area heading toward an evil scrapbook (pg. 142), which Danny instinctively knows he should warn Jack away from (“some books should not be opened”), but Jack does grab it on page 143 and Tony begins to jibber the same “incomprehensible thing over and over”, which is “This inhuman place makes human monsters.” And doesn’t that sound like the Goya title?

Now, if you read my Golden Shining analysis, you know that 143 is what you get from adding ten Fibonacci numbers together (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55). And if you know about Fibonacci, you know that that sequence creates a “golden spiral”, which is a pattern that shows up in real nature (as well as in much art, as we’ve seen). So it seems like this warped Goya message from Tony is a reaction to Jack grabbing the Overlook scrapbook. If Tony is using this thing that seems like a scientific expression of “reality” at Danny, what would it be used to dispel?

If you want the details for what I’m about to say next, go read the analysis for pages 152–166, which is all of Chapter 18: The Scrapbook. But the simple version of my findings is as follows. The scrapbook is a collection of newspaper clippings, detailing the hotel’s progression from inauspicious beginnings down into gangland murders and possible mafia ties among the ownership. Jack’s almost fired from his caretaker position after revealing (to Ullman and Al Shockley) his plan to write this history into a book. His obsession and passion to find meaning (ever elusive to Jack) among the papers in the basement plays a big part in why he eventually becomes slave to the purposes of the big house. King gives real dates to mark the progress of the Overlook, and it’s not hard to look them up, though it’s possible, even very likely, that Wikipedia is limiting its entries to only the most significant events. Even so, three of the dates given tie to the JFK assassination, and the ensuing conspiracy theories that grew up around the event. What’s more, some have compared movie Ullman to looking like JFK, and novel Ullman drives a Lincoln Continental (pg. 100), the car that JFK was assassinated while driving. Ullman uses the phrase “continental” to describe the “manners” of Truman Capote (pg. 95), a man whose first name happens to be the same as the last name of the president two jumps before Kennedy.

So, what Tony wanted Danny to save Jack from (symbolically) was getting lost down the rabbit hole of a conspiracy theory that will never be proven, one way or the other. It’s not that JFK wasn’t killed, and it’s not that his death wasn’t suspicious (in fact the dates of the Overlook clippings point to events that speak to how suspicious it was), and it’s not that his death wasn’t important. What could be more important, or damaging to democracy, than the slaying of an elected official? But what Jack plans to write about the hotel isn’t especially significant, and, as Ullman points out, is all public knowledge. As the story progresses, Jack’s book plans for the Overlook become openly autobiographical (pg. 222) – unlike his play, which is only quasi-autobiographical (pg. 105–116) – and as he obsesses over this new, fruitless endeavour (if he had put the JFK part together, what would he have done with that information?), awful things begin to happen to his family.

But we’re not done with Fibonacci. On page 197 he gets one more blast of “This inhuman place makes human monsters.” And that’s exactly 54 pages since the last one. So the first blast was 143 (or ten Fibo-values added together) and the second blast is 54, which is eight Fibo-values added together. A ten and an eight. And with only 250 pages from here to the end, there’s only eleven Fibo-values where this phrase could pop up again, and keep this pattern consistent. And you know where it pops up again?

Nowhere. Or at least nowhere that I could see.

You know what does happen, though? A mere 232 pages after page 197 is page 429, and that’s the page that Danny spontaneously, and for no other given reason (he has a few dreamy thoughts about the “basement” on preceding pages), figures out “what was forgotten” and screams into Jack’s face that the boiler is about to explode and destroy the Overlook. And 232 is the eleventh Fibo-value. So that’s ten (143), eight (54), eleven (232).

On page 177 we learn that the date is November 7 when Jack goes to confess his plans to Ullman, almost ruining his career. The next 20 pages are from the same day, and it’s only at the end of page 197, after receiving his second Goya shine, that Danny falls asleep “sometime after midnight”, meaning the date that marks the end of the 10-value and the 8-value is an almost invisible, undetectable November 8th. So perhaps it’s simply that “November” that’s nodding us toward going to the 11-value (pg. 429) for Danny remembering “what was forgotten”, which, remember, was the thing he saw in his vision, circa page 143 (before forgetting what it was upon awakening).

But why would Danny suddenly just “remember what was forgotten” on page 429? Like, there’s nothing in the narration that sets it up or explains it. Could Danny have somehow understood that he was on the eleventh Fibonacci beat, and that’s what drew his mind back to page 197, which connects back to 143, and then he saw “what would be forgotten” and knew (finally, in waking life) that it was the boiler, and to scream this in Jack’s face? Wouldn’t this 5-year-old have to not only understand Fibonacci, but also that he’s a character in a book with 429 pages? And that’s patently absurd.

But isn’t the central struggle of Jack Torrance to write his play? And in his play, Jack can’t quite seem to identify completely with Denker, the cruel headmaster, nor with Benson, the brutalized student (pg. 105–116). He’s able to see how the student he brutalized, George Hatfield, bears a symbolic relationship to the Benson character, but he can’t seem to face his own Denker-ness. As he struggles to do so, two things happen: one, he’s confronted more and more by the spectre of the memory of his wicked, abusive father, and two, he’s absorbed more and more by the false patterns in the scrapbook (and all the surrounding detritus). The Overlook draws him away from his reality, which for him is figurative (he can’t see that he’s a character in his own play), but in our reality is literal (he can’t see that he’s a character in a novel). Watson even seems to be drawing his attention to it on page 21 when he says, “Say, you really are a college fella, aren’t you? Talk just like a book.” This is the struggle of all characters in all novels, of course. And I suspect it would get tiresome if every character in every novel did know this, and constantly bemoaned the fact. But since a major component of what “the shining” represents is our ability to put images and ideas in one another’s minds, just as novelists do with every novel they write, Danny being able to “shine” like no one Hallorann’s ever met before (pg. 80), does seem to reflect Jack’s struggle. Jack can’t finish his play because he can’t really shine, or, failing that, he can’t see that he’s a character even in his own play. And while there’s never a moment where King writes Danny realizing that he’s a character in a novel, this page 429 moment works as if he does.

That’s sort of a pet theory. But it’s the best I could come up with to explain King’s very deliberate pattern, and its effect on Danny. If I am correct about it, it might explain some of the references that Kubrick seemed to be making to the real lives of his actors, as if attempting to do a similar thing – showing how Jack Torrance is seemingly oblivious that he’s being played by Jack Nicholson.

There remains this issue of the ten-eight-eleven, and the Nov. 8th business. That date would be rendered as 11/8 on any given year, so maybe 11/8/10 is a specific date King wanted Danny to “remember”. A quick look across the various centuries (1910, 1810, 1710, etc.) revealed nothing of substance. And the film makes references to things dating back to the 13th century (nothing from 1910 ID’d as of yet). Barring a Jack-Torrance-style research project into all the November 8ths of the last millennium, which I’m not willing to do, we may never know.

But the novel mentions a ’10.

1910.

That was the year the hotel first opened to the public (pg. 24), and we learn that from the son of the man who built the hotel, Watson, who shows Jack the boiler and who warns excessively of its capacity to blow (pg. 16–20). In fact, he tells Jack that the boiler is rated to “250” (pounds of pressure per square inch), but that he wouldn’t want to stand next to it past “180”. Page 180 is when Jack decides (again, for no good reason) to detonate his relationship with Ullman, which he instantly regrets afterward, and is the event that, more than anything else, keeps the Torrances from leaving the hotel (both Jack and Danny feel that they’d rather risk the nightmares and the pain of this place than try to survive anywhere else). And page 250 marks the end of Danny emerging mentally from his 217 experience and Jack deciding to visit the room himself, which is the event that triggers Jack cheating on Wendy. In the film he literally cheats on her with the ghost, and in the book he cheats on her in vaguer terms, simply lying about what he saw in 217, selling out their wounded son as insane. It can’t be like the hedge animals or even the nature of his interest in the scrapbook. Danny’s trauma makes it necessary for Jack to either get Danny out…or sell him out. And he chooses the latter.

So maybe the hotel opened on Nov. 8 and maybe it didn’t. We’ll never know. But it was the day that marks the page (197) upon which Tony’s last Goya warnings occur. And 24 pages after that (24 being the page with Watson’s “1910” on it) is page 221, the page that Wendy falls asleep on while pondering the work of Bach and Bartók, two composers thought to have composed their music according to the Fibonacci sequence, and, as far as I know, the final direct golden spiral reference in the book.

The golden ratio is what helps Danny realize the reality of the fantasy he’s in.

And also, aside from the constant refrains of “Doc” and the occasional reference to a “witch” (and, of course, a whole lot of references to “snow” and “white”), there’s no overt reference to Snow White in the book. So how perfect is it that Danny’s mystical saviour page is 429? As a time code, 429 is 7:09, and 709 is the Aarne-Thompson code for Snow White.

ESCAPING THROUGH THE NYET

It hit me when editing the mirrorform that Jack’s blood-spattered face feels positively on purpose. The gout of blood on the wall behind his right eye almost seems to give him lashes like Alex DeLarge has in A Clockwork Orange – DeLarge who is known as Alex Burgess in the film (the book was written by Anthony Burgess).

On page 258, Jack recalls that his favourite story he ever sold was called The Monkey is Here, Paul DeLong (DeLong sounding like DeLarge – though the De Long Islands are where the doomsday device from Dr. Strangelove is built (specifically Zhokhov Island)). He relives the story in his mind (a child molester (like Humbert Humbert?), named Paul “Monkey” DeLong, is released from prison by an overlord named Grimmer) and realizes that he sympathizes in different ways with all the different characters, knowing that that sympathy came from his own lived experiences throughout life. On the next page, he realizes that he’s come to loathe the “goody two-shoes” protagonist of his quasi-autobiographical play, Gary Benson, and is coming to realize that the villain of the play, Mr. Denker, is much more the character he admires, a Mr. Chips kind of guy. I think the point here is that Jack was more able to write real characters when he was more able to feel like a real person himself, when his writing reflected real life. Benson and Denker are starting to seem too black-and-white, but perhaps only because he can’t face the growing darkness within himself, and not because these characters aren’t true to life in their mechanics. And, fun fact, there’s a painting just outside room 231 (the room I believe the Overlook swallows Jack’s soul into) called The Battle of Long Point, and at the other side of that hallway is one called A Man of Van Diemen’s Land, which could be referencing a minor genocidal moment of history involving a guy named Nicholson and a guy named Jack of Cape Grim.

Paul “Monkey” DeLong sounds like “Paul monkeyed along” in English, and I can’t help wondering (given all the other Beatles references) if that’s meant to say “Paul McCartney monkeyed along.” What exactly that implies I’m not sure, but Paul is correlated to Jack in the Abbey Road Tour, the Let It Be analysis, and the Sgt. Pepper analysis. So, that might finally explain how Kubrick knew that Jack Torrance was meant to reflect Paul McCartney.

As for “Grimmer”, that’s a name that sounds an awful lot like Grimm, as in Grimm Fairy Tales. And 258 (the page that describes all this, remember) is not a main story code for anything, but the closest one to it is 253: The Little Fish Escapes Through the Net. Wendy actually reflects on page 62 that the sun (shining through a distant waterfall on the way to the Overlook) resembles a “golden fish snared in a blue net” right before her first thoughts turn toward the Donner Party. A guy named Alexander Pushkin wrote a similar tale, The Tale of the Fisherman and his Wife, and on page 163 Jack learns that one of the mafia goons who worked for the Overlook was named Carl Prashkin. The opposite page from 163 is 285, whereon Danny compares himself to Patrick McGoohan’s character on Secret Agent in his fights against the KGB nogoodnik, Slobbo, who uses his “Russian antigravity machine”. I can’t find any evidence that there was ever a such a character or machine on the show, but there is an anti-gravity machine in Licenced to Kill, a James Bond parody. Secret Agent was noted for its similarity to the Bond franchise, and Wendy sits next to a copy of the Ted Mark novel Dr. Nyet, which parodies Bond (in fact, the moment opposite the appearance of the novel is Jack passing Danny’s hiding spot on his way to kill Dick).

The Little Fish Escapes Through the NYET!

But yes, the reason Danny is comparing himself to McGoohan is because he’s in a concrete playground ring that’s partially buried in snow, where he meets the voice of a child who seems to be buried there too, and wants Danny to play with him forever and forever and forever (pg. 288). In fact, the page opposite Wendy’s “fish” vision is 386, where Dick has driven almost off a cliff before a snow bank caught him. He’s on his way up to the Overlook, same as it was for Wendy. Hallorann is saved by a man named Howard Cottrell, who shares a name with a man from the same era as that Nicholson from Van Diemen’s Land, and who had basically the exact opposite life story as the one from that etching.

I guess what I’m wondering is: is King suggesting that Jack used to understand the mechanics of story, the mechanics of Aarne-Thompson/Grimm storytelling, and how to combine that with his own experiences to make good writing, and now he just wants to use writing to exorcise his demons, and to glorify his lesser nature? That’s what Grady is admonishing him to aspire to in the accompanying scene here.

Sometimes you just gotta “correct” some history, Jack!

JACK’S (BROKEN) LADDER

In the film, there’s a repeating song called Dream of Jacob (about Jacob’s ladder from the bible), which, in my view, draws our attention to the film’s repeated use of numbers that mean different things in different circumstances. Torah scholars believe that the rungs on Jacob’s ladder reflect years, so when an angel goes up and down 70 rungs of a ladder, that represents the 70-year exile of the Jews. Well, Shelley Duvall was 30 years old when racing to Jack Nicholson’s side, passing the 23×7-stair Grand Stair in the lounge, as Dream of Jacob played overhead. But there’s a lot of other ways the film plays with numbers.

For instance, the mirrorform does some cool things, like when Hallorann’s showing off the kitchen, there’s a 9-rung ladder, which becomes something like a spine for the store-room-trapped Jack on the other side of the film, as he speaks to Grady. Grady who murdered his family 9 years ago. So a 9-rung ladder being Jack’s spine would seem to imply that he’s becoming an agent of the hotel, a replacement Grady.

And if you’ve seen my intro documentary, you know that certain scenes and songs play for significant lengths of time, like how Jack’s experience inside 237 is 273 seconds long.

Well, the book does this in a million ways that you’ll only appreciate if you sift through the page-by-page analysis (I could make a list, but that sounds thankless and exhausting). So I’ll just zoom in on probably the best example, since it has to do with ladders.

The first page of Jack being isolated and alone at the hotel is page 105. He’s up on the roof of the hotel, fixing the shingles (one of Ullman’s only stated assignments for Jack), revealing a wasp’s nest that gets Jack a mean sting. He pictures the 70 foot drop between the edge of the roof and the ground, should the wasp have caused him to run and fall. He pictures that number again on 108, 109 and 110. And on 107 he imagines himself racing down the ladder. In every instance he’s contemplating something about the nature of the blinding pain of a wasp sting, and how no one could be blamed for reacting to such a terrible sensation, even if it meant plummeting 70 feet. At the same time, he’s reflecting on the nature of his play, and how, despite the fact that the real history of his altercation with George Hatfield makes him look like the villain of his play, Denker, he is in reality more like the hero of his play, Benson…who he also sees as being like Hatfield. So, both he and Hatfield are like the hero of a story about a cruelly abusive schoolteacher. Who does that make Denker? Well, probably the wasp-stings of the world. The cruel misfortunes laid on us by the true puppet master of all puppet masters: life.

So let’s imagine that the pages are the feet. And that by falling “70” feet, Jack would be falling back 70 pages. On pages 38–40 Jack is reliving an experience he had with his friend Al Shockley, who owns the majority of shares in the Overlook. They were driving drunk along the highway US 31 into “Barre”, when they strike a riderless bicycle without noticing it was in the middle of the road. This fills them with enormous guilt, despite the fact that no child’s body can be seen.

And if we interpret this repeating highway number, 31, as a signal to go back 31 more pages, this brings us to pages 7–9, which mark the start and end of Ullman’s account of the Delbert Grady murder suicide (Ullman who is played by Barry Nelson – Barry is pronounced the same as Barre).

So we’ve got Jack denying that he would ever become like Grady (7-9), and Jack denying that he’s anything like the character who most resembles him in his own play (106-115), linked by a highway (31) and a ladder (70). And right in the middle is Jack participating in an event that, while not completely damning, makes him look about as irresponsible and guilty as an otherwise reasonable person can look.

Note too that the numbers in 70 and 31 can make 137. In the film, the two major numbers are 237 and 157, 157 being 2:37-worth of seconds. The evil room in the book is 217, and, as we’ve seen, Danny enters the room on page 217. Well, 137 would be 2:17, and page 137 is the start of Danny’s interview with Dr. Edmonds, the doctor who will employ armchair skepticism to dismiss Danny’s ability to read his mother’s thoughts in the other room, gloss over Jack’s admission of physical violence against his son, but also ask Danny to call upon Tony, causing him to descend into the dream world that Danny enters on 143, creating a component of his Fibonacci lessons. Similarly, in the film, Danny receives his escape key right before the doctor appears (it’s onscreen at 10:37, in fact, and 13:07 is the start of the doctor asking “Do you remember what you were doing just before you started brushing your teeth?”, the question that introduces Tony), and his lesson key is inside room 237. In both instances, Dream of Jacob is playing. The only other time the song plays is at the beginning of the shot of Danny playing with his toys outside room 237 (57:10), continuing through his entry, Wendy in the boiler room, Jack’s murder nightmare, and Danny emerging from 237.

But yes, it would seem that 137 speaks to the “science” side of things, while 217 speaks to the “art” side of things (Danny is bombarded by imagery from children’s stories while he moves through the area). So perhaps these two “ladders” of page counts, broken in the middle as they are, speak to Jack’s inability to use science or art, or “reality” and “fantasy” to escape his own predicament. And isn’t that what the Jacob’s Ladder story is all about? Learning that dreams have meaning that can aid us in dealing with reality? If Jack was like Jacob, he might’ve learned that “The lord is in this place and I knew it not” (Genesis 28:16). Instead, he simply learns that the Lloyd was in this place (pg. 237-241, 341-344), and he knew it not.

Also, let me point out that there’s a mirrorform bit that goes with this: page 343 is the mirror page for 105, the first of Jack’s 70-foot drop pages. And on that page, he’s at the ghost ball, about to drink his first “real” ghost drink from Lloyd, when he gets a flash of the incident on the highway, of him and Al smashing the riderless bike. Then, opposite the sequence of Jack and Al smashing the riderless bike (pg. 408-410) is the bulk of Jack’s attack on Wendy in Suite 3, which ends with Hallorann’s interrupting arrival. And we know from an earlier chapter showing Hallorann’s struggle to reach the hotel (pg. 404-405), that he encounters a hedge lion in the middle of the path ahead of him. It lunges at him while he rides, and he’s brought off the snowmobile into mortal combat. On page 412 King even informs us that this is happening in tandem with Wendy’s struggles to elude Jack in Suite 3, so, yes, Dick is having something of the opposite experience that Jack had on 38-40, not striking a riderless bike, but being struck off his snow-bike (his controls are described as “handlebars” – which is the very part of the bike that “starred the windshield” of Al’s Jaguar) by a soulless ghost monster, and it’s happening “off-screen”, so to speak, in the mirrorform. Perhaps to highlight how different, how inverted Dick’s experience and Jack’s really are. Then, mirroring over the Grady discussion on pages 7-9 is Dick entering the Overlook equipment shed (pages 439-441) to look for blankets to keep Wendy and Danny safe, but he gets distracted by the roque mallets on the wall, and becomes momentarily possessed by the urge to slay the two innocents, as Overlook thoughts bombard his mind. Fun fact: on page 6, Jack even contemplates the equipment shed, as he ponders what other wonders the Overlook might have in hiding. And you know, since the ghost drinks are what leads to Grady slandering Hallorann, and implying Jack should kill him along with Wendy and Danny, I’d say this Jack’s Broken Ladder phenomenon is a bit like a Goofus and Gallant saga for Jack and Dick. One with biblical implications.

A CHAIN OF CHANEYS

When I was working on my page looking at the ghost who calls “Great party, isn’t it?!” at Wendy near the end of the film, it hit me that I should try to find where this happens in the book for additional insight. What follows here is the second half of what you’ll find by clicking that last link.

Basically, my original theory was (and basically still is) that GREAT PARTY ghost is the actual Charles Grady. He appears right as Ullman is saying, “My predecessor in this job (close up of “Great party, isn’t it?”), hired a man by the name of Charles Grady (wide shot as seen below) as the winter caretaker…”

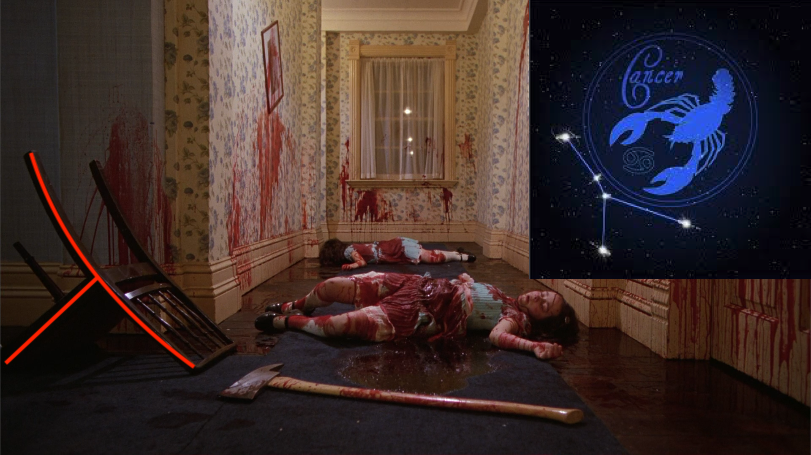

So I’ve considered a bunch of things, like how there’s three paintings that should be behind this ghost that disappear once he’s on screen (which I believe could represent the murdered wife and daughters).

Or the fact that the painting next to him is called Makah Returning in Their War Canoes by Paul Kane. A “cane” is what Jack’s father Mark uses to beat in Jack’s mom’s skull and torso at the very centre of the novel (pg. 224), and there’s 24 rowers in the canoes seen in the painting.

There’s also the fact that this guy is standing where the bloodfall elevator will be when this hall transforms into the bloodfall hall. Jack and his father play something called the “elevator game” (pg. 223).

But there’s also less direct phenomenon that occur around the spot where GREAT PARTY ghost appears. So, when Jack is on his way to the ghost ball, standing in the spot where Wendy will encounter GREAT PARTY, he passes a painting by Lawren Harris called Maligne Lake, Jasper Park. This painting depicts, among other things, two mountains of note: Samson Peak and Mt. Charlton in Alberta, Canada (Alberta being the feminine form of Delbert (Grady)). Charlton sounds like Charles (Grady), and Samson was Judeo-Christian mythology’s answer to Hercules. So, fans of my Pillars of Hercules theory will understand how that applies to Grady.

It’s also probably not lost on you that this painting, which never appears in full (this is the best view of it), hugely resembles the first shot in the film. So just like Wendy being halfway through Catcher in the Rye (in fact, she’s at the 5/8ths mark) 4 minutes past the beginning of the film, we’re now 10 minutes past the middle, and we’ve got this echo of the first shot in the film. Jack is starting over, becoming Samson (a man betrayed by his lover), becoming Hercules (a man who murdered his wife and children), becoming…Grady.

Now, we only see a few people ever physically pass this spot clearly (like Ullman and Watson, before meeting Jack for the tour), and only one that we see pass the spot very clearly (3:25-3:29). And that’s this guy (with Red Maple by AY Jackson behind his head).

Who is that guy? I don’t rightly know. But he comes from around the corner, from the direction of GREAT PARTY/Grady, and we do see him one more time (11:02-11:12 and 11:14-11:19). When Jack is calling Wendy about getting the job, standing over the model labyrinth, as Ullman and Watson stand in their Carson City formation.

I do have one idea about that guy’s identity, actually. We know that the staff wing is supposed to be on top of the lobby, by the way Danny pops out the window right above the lobby. And, as discussed in my Tower of Fable section, we know that when Danny stops to encounter the Grady twins in the staff wing hallways he’s right above where the model labyrinth usually is (right next to Stormy Weather). Well, at this point in the film, the model labyrinth is pushed slightly east of where it usually is, which would put it and the maybe-Grady guy directly beneath the thing Danny turns away from to meet the Gradys, which is a dumbwaiter.

Sorry, I just checked the site exhaustively for a shot of the dumbwaiter to no avail, but if you can take my word, it’s there.

Anyway, on page 97 of the novel, Danny gets really excited by the fact that their apartment has a dumbwaiter in it, comparing it to Abbott and Costello Meet the Monsters. The movie he’s trying to reference is actually called Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (the “Monsters” version was a TV documentary about the film), which featured Lon Chaney Jr. reprising his role as Larry Talbot, the Wolf Man. Chaney also played the villain in the film version of a novel Jack’s reading on page 117, Welcome to Hard Times. And Jack actually tells Al Shockley that he looks like Lon Chaney’s character in Phantom of the Opera when they both decide to get sober, on page 42 (for the record this Lon Chaney was Lon Chaney Jr.’s father). I only did a page-by-page analysis of the first half of the novel, so it’s possible there’s other references to the Chaneys later on, but what’s cool about these three allusions is that that the opposite page to 117 is 331, where Jack has just saved the hotel from exploding and thinks to himself that, since he’s just “served the Overlook” now “the Overlook would serve him”. The opposite page from 97 is 351 where Jack is meeting Grady at the ghost ball, and Grady’s telling him he’s a “true scholar” who could go “to the very top” of the Overlook’s “organizational structure”, and Jack agreeing to “deal” with Danny. So, even though Grady has appeared as a servant who, it seems, lives only to serve Jack, in five short pages he’s getting Jack to agree to corporal punishment. The opposite page from 42 is 406, and that’s the page…where a man in a “green ghoulmask” pops out of a random door somewhere near their apartment and screams, “Great party, isn’t it?” in Wendy’s face, as she scrambles to seek refuge from Jack’s flailing mallet.

Oh, okay, it seems I’ve stumbled on more connections. Lon Chaney the elder played Blind Pew in the 1920 film version of Treasure Island. On page 372, while Wendy and Danny are dragging Jack to the pantry, Wendy reflects: “The surroundings reminded her of the seafaring captains cry in Treasure Island after old blind Pew had passed him the Black Spot. We’ll do him yet!” On this same page Jack mumbles a line in his sleep that we recognize as something his father said to him once, which he last recalled just before saving the hotel from exploding (page 329). This is the last clear reference Jack makes to his father in the novel, and the opposite page, 76, features the first reference to his father that Jack makes to himself when Hallorann asks him if Watson isn’t the “foulest talking man” Jack ever “ran on”, and Jack reflects that his own father holds that title. So, Wendy gets a random thought that connects to the father (Lon Chaney) 331 pages after Jack compared Al to the father. And in the middle are the (much more obscure) references to the son.

And then I noticed that Chaney Jr. worked with André de Toth, the director of Carson City, on a film called The Indian Fighters. That film starred Kirk Douglas (the star of Kubrick’s Spartacus), and featured Chaney as a villain named Chivington. De Toth’s film appears to be relatively sympathetic to the indigenous cause, but is part of that well-trod sub-genre of westerns where our hero the white man falls for an indigenous girl, and murders other indigenous people on her behalf. See, it’s okay, cuz he’s so broad minded…he could even fall in love with an indigenous person! But whatever, it was 1955. And it had the nerve to name the villain after one of the most villainous Americans of all time, John Chivington, who perpetrated the Sand Creek massacre. This is probably the strongest connection I’ve yet made between The Shining and that genocidal moment in American history. What’s kind of amazing is that de Toth’s film inside The Shining is right beneath Alex Colville’s Woman and Terrier, which he called his “Madonna and Child”, so just as there’s all this Chaney father-son subtext, Kubrick cozies it up to a mother-son subtext. What’s also amazing is that there’s a painting inside room 237 by Nadia Benois, whose family owned what was called the “Benois da Vinci”, a “Madonna and Child” painting by Leonardo da Vinci. And she was the mother of the only actor Kubrick ever directed to Oscar gold, Peter Ustinov (for his work in Spartacus). So, both of our indirect Spartacus references are occurring in direct connection to a parent-child image.

For the record, the other feature film in The Shining is Summer of ’42 and its director, Robert Mulligan, directed Robert Redford in Inside Daisy Clover, and on page 111 Jack compares the student he beat up, George Hatfield, to Redford, right before comparing himself to Hatfield. So Jack sees himself in Redford, and Danny and Wendy sit down to view a film by a director who worked with Redford. Also, on page 273 Jack thinks he’s going to murder George Hatfield in a dream (with his father’s cane) before he transforms into Danny at the last second, before Jack can stop himself.

Okay, so that was quite a walk to get to my point, which you’ve probably forgotten by now. My point is, there’s obviously no place for the dumbwaiter outside Suite 3 to end up, given what we know about the construction of these floors, so our guy hovering over the maze would most likely bear a connection to this pattern series. But Lon Chaney Jr. was dead before even before the novel was written, so what I’m wondering is…could this be André de Toth?

There aren’t a lot of pictures of him online. And the guy in the movie is never both close to the screen and in focus. But it would make a kind of cool sense, given his connection to all this. Perhaps his leaning over the labyrinth in between two men mimicking the two men in his own movie would suggest a film director’s “parental” dominance over a film.

But de Toth’s connection is to Chaney Jr., whereas “Great party” ghost in the novel is directly across from page 42, where Jack compares Al Shockley to Chaney the elder.

So perhaps the answer to the identity of GREAT PARTY ghost lies in the fact that the actor who plays him is Norman Gay. The Torrances own the autobiography of Tenzing Norgay (Nor(man)gay), the first man to climb Mt. Everest, cowritten by James Ramsey Ullman. So, if the connection between Nor-Gay and Norgay is intentional, then there’s a thing there about men who climb mountains, and the different outcomes that can occur. Norgay held it together. Nor-Gay blew his brains out. But that connection to Ullman makes it seem like what we really have going on here is a connection to every father figure in Jack’s life, all of whom have some thumb in the Overlook pie, except for his own father, Mark.

Actually, Mark Torrance’s full name is Mark Anthony Torrance, and Mark Anthony was a supporter of Julius Caesar. And André de Toth directed Gold for the Caesars.

So I don’t know. Maybe it’s as good as “whatever father figure works for you”. Maybe when we can ID that mystery sketch to his side, and the artists behind the landscape and dog portraits behind him we’ll get a better idea.

I have one more thing to tack on to this Frankensteinian father-son argument, which starts with the fact that Jack’s father’s name is Mark, right? And Jack is from Berlin (pg. 75). Well, that’s Berlin, New Hampshire, but we do learn (pg. 157) that Horace Derwent’s fortune came in part through a patent on a bomber carriage that rained hellfire on the more famous Berlin, where Hitler blew his brains out. So that got me wondering if Mark, whose hellishly traumatizing parenting style warped little Jackie’s mind inexorably, was meant to sound like the German word for money, the Deutsche mark. In fact, Germans simply call them marks.

Well, getting away from the more existential crisis Jack faces (that he’s a character in a book), his more substantial problem is money. His temper loses him his job, and he’s had to take the only thing available to him. Even after he and Wendy accept their fate, they both find themselves wondering what’s gonna come after the Overlook experiment. On page 36 we learn that Jack’s got $600 to his name (which would be about $2600 today, for the record). On page 188 Jack has a humiliating reflection that if he doesn’t play his cards right with Al, he and Wendy and Danny could end up like a “family of dustbowl Oakies” heading for California in their last-legs beetle – a pretty clear reference to The Grapes of Wrath. His agent suggests he look for inspiration for his play in the writings of the Irish Socialist playwright Sean O’Casey (pg. 106) but Jack seems to have no intention of investing in her advice. When he boasts of his two twenties and two tens to Lloyd on page 239, he pulls out a bottle of painkillers instead, and can’t even mask his angry humiliation from his own fantasy barkeep. When he finally can pay for his ghost drinks on page 341, Lloyd tells him his money’s no good here (pg. 342). In fact, page 342 is the mirrorform page to page 106. Jack doesn’t want a hand out. He wants to pay for what he takes from the world, no matter how rigged the system, no matter how gluttonous the overlords. Every time he thinks about money, he quickly moves into either his guilt about being an alcoholic, or just wanting another drink. If he could move past what Mark has done to him, could he escape his ultimate vice?

And the question remains, does he want to pay for what he takes from this world, because that’s what’s right? Or has money (Mark) traumatized him into the role of The Queen’s Dog (a fable referenced in the film), where he has no choice but to serve it all the days of his life? If that’s the case, then the Overlook is offering him a kind of fantasy life alternative, where nothing will ever cost him anything ever again. It’s a life he craves, in a way, how seduced he is by the hotel’s opulence, and Grady’s insinuations about the management sweeping him straight to the top, if he plays his cards right, and gives them everything they ask for.

This brings me to the discovery I made that inspired this train of thought. It has to do with the Twice-Fold, which is the mirrorform folded in half again, bringing the middle of the action to the beginning, so you get four layers of action.

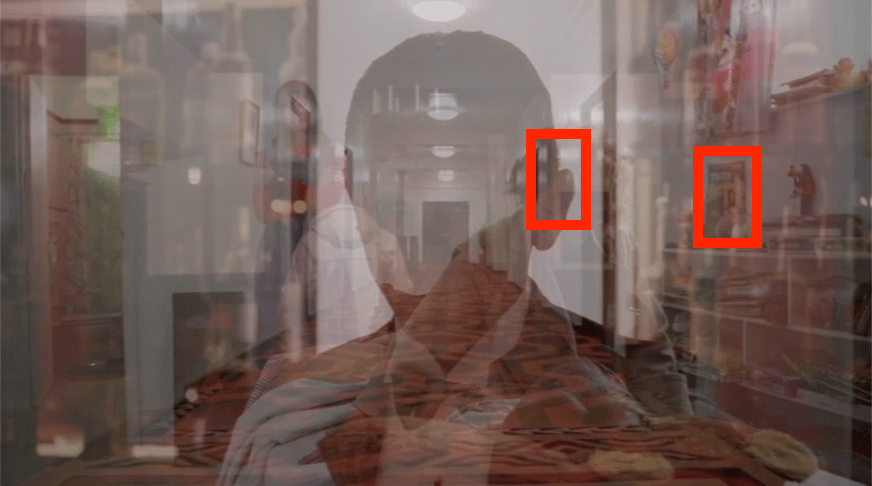

Now, Lloyd says, “Your money’s no good here” at 13:15-13:17, which, if you’ve seen my intro documentary, you’ll recall are the worst years of The Great Famine, when people across Europe started eating each other to survive. It’s believed that the Hansel and Gretel fable comes out of that period, perhaps to normalize or soften the commonplace cannibalism, and perhaps as a story about the glamour of a house made entirely of food, but to warn children off of such places. The other three layers here feature the doctor asking Danny if he remembers what he was doing before he started brushing his teeth (Danny has a Candyland game beside his head in this moment), Danny being tempted into room 237, and Dick is seconds away from getting the chop. (Ignore the red boxes, they’re from a different point from the Twice-Fold analysis. Also, this isn’t quite the right moment, but it looks virtually the same. The big difference is that Danny’s Apollo 11 shirt is visible in the corrent moment.)

Dick is chopped directly beneath a painting of Chief Bear Paw, who was from the same clan, Bearspaw, as Chief Walking Buffalo, whose portrait is directly below where Wendy clubbed Jack atop the stair. And Walking Buffalo’s proper name is Tatânga Mânî, which is pronounced the same as “money” in English. So if Mânî was giving power to Wendy’s defeat of Jack, that “money” is no good anymore for old Dick Hallorann. In fact, if Jack becomes the minotaur for the hotel, as I believe he does, it’s worth highlighting that Mânî means buffalo. Jack’s buffalo is no good here, so he’d better become a better one. A cannibal one.

Also, according to my Avenue of the Dead theory, the Overlook is modelled after a particular collection of pyramids in Mesoamerica, which puts the Grand Stair (and the spot Dick is killed) in the same spot as the Pyramid of the Moon. And Mânî looks and sounds an awful lot like the Norse moon god, Máni. Your moon is no good here.

So it might not be a simple overlay that it looks like Lloyd’s pushing Danny toward 237 as he’s rejecting Jack’s money. It could be that the Overlook is overpowering both the Buffalo energy that could’ve protected Dick, and the moon energy that could’ve protected Danny.

But perhaps the ultimate point here is that Jack needed to face his true maker: on the literal level, Mark Anthony Torrance, and on the figurative level, Stephen King.

EVOLUTION OF A MASQUERADE

There’s a curious phenomenon in the book of minor characters having very similar names. There’s a “Mrs. Brant” who makes a fuss about the Overlook not taking her American Express on closing day, before Danny shines a thought from her mind, lusting after the Overlook’s “car-man” (pg. 66–70), a guy Hallorann later identifies to Danny as “Mike” (pg. 82). Then, on page 138, Danny refers to a child from his left-behind Jack & Jill Nursery School, “Brent”, to explain to Dr. Edmonds how he knows what epilepsy is. Then, on page 178, trying to get ahold of Ullman at his Florida resort, and the receptionist wonders if he’d rather speak with “Mr. Trent”. And on page 222-225, we learn that one of Jack’s older brothers (who dies in Vietnam), was named Brett. And his other brother’s name…was Mike (pg. 222-226). Which is also one of the names Dr. Edmonds throws out as a replacement for “Tony” (pg. 147), when he’s talking to Jack and Wendy. He’s asking if Danny realizes that the name “Tony” was most likely inspired by Dan’s own middle name (Daniel Anthony Torrance), whereas a name like Hal or Mike or Dutch would’ve held less significance. Jack’s own full name is John Daniel Edward Torrance. So if “Edmonds” was meant to resemble “Edward”, then Jack’s own middle name is like a mash-up of these two concepts. The Edward is warped into Edmonds, perhaps because Jack will accept what this learned, science man lays out for him, but the Daniel is direct, and mirrors Danny’s own assignment of “Tony” to his higher-self (as if Jack was trying to create a little “Tony” for himself). But Danny doesn’t try to warn Jack about the hotel’s ills directly, perhaps resulting from the “break” between father and son (literal (Danny’s arm), and figurative (Tony replaces Jack as a guiding father figure)). Also, later, when Jack’s investigating the mafiosos who stayed at the hotel (pg. 162), one of them, Charles “Baby Charlie” Battaglia, is known to have slain a Jack “Dutchy” Morgan. And then there’s Peter “Poppa” Zeiss (“Baby” “Poppa”), who has a story to tell, but of greater concern to me is how the Torrances use Jack’s Zeiss brand binoculars to inspect a gang of five motionless caribou outside the hotel (pg. 213) not long after Jack learns all about the five murderous gangland-types who might be employees of the Overlook’s ownership, and really not long after he was attacked by a hedge dog, hedge buffalo, and three hedge lions (pg. 206–209).

Then, consider that Mike and Brett and Jack’s father is “Mark”. Or that the other teachers at Jack’s old school are Zack and Vic. Or how a man on the board there is Harry Effinger, while one of the hotel’s ghostly ex-(?)-owners is Horace “Harry” Derwent, while another ex-owner was Robert Leffing. Dr. Bill Edmonds and Bill Watson have the same first name. Or consider that Danny is clutching his “Winnie” doll while remembering his friend Robin, whose dad “LOST HIS MARBLES” (and isn’t Winnie-the-Pooh a make-believe character in the mind of Christopher Robin?). This goes on and on, and works in all kinds of mysterious ways.

But I think the point (besides helping us to better understand the nature of the various characters and their purposes, via cross-reference), is to show how the life and universe of Jack Torrance is a novel universe. It almost gets silly how much everyone possesses a name that means something, connects to reality, or echoes another character’s name. But isn’t that what we expect from drama? That a writer should take the care to consider what each character’s life is all about, and to construct connections that help the reader to understand what the writer is trying to say about life? And what it the nature of Jack Torrance’s life? He exists in a reality that mostly resembles our own evolving universe, but it’s not really an evolving universe, it’s inert and hermetically sealed by publication. And if he could but realize these things for himself, he would see the design, the superstructure. It’s up to those of us who know the difference between fantasy and reality, between masquerade and society, to see it for him.

THE STORY CODE PHENOMENON

What follows here is an analysis that grew spontaneously out of analyzing a moment from my mirrorform section. I’m not going to edit it for form. Just understand that the next paragraph begins where everything began over there, as I was going beat-by-beat through all what you can learn by studying the film forwards and backwards. This might sound like some hot nonsense if you aren’t familiar with certain of the concepts. Also, I was trying to keep the stuff on this page relatively simple, and this one gets real complicated real fast. You’ve been warned.

I didn’t want to talk about too many of the cool things you’ll find over on the disappearances analysis page, but I love this one too much. As Jack first starts to act weird, asking Wendy what she “[wants him] to do about” the coming storm, there’s a table and chair behind him that go missing for just this shot (see below), and on the opposite side of the film, the thing that fills the space for that moment is the snowcat at Durkin’s that Dick will ride to the rescue, and that Danny and Wendy will ride to safety. So Jack’s first seeming weirdness accompanies a visual weirdness, and the mirrorform seems to scream at Wendy “Get out, girl!”

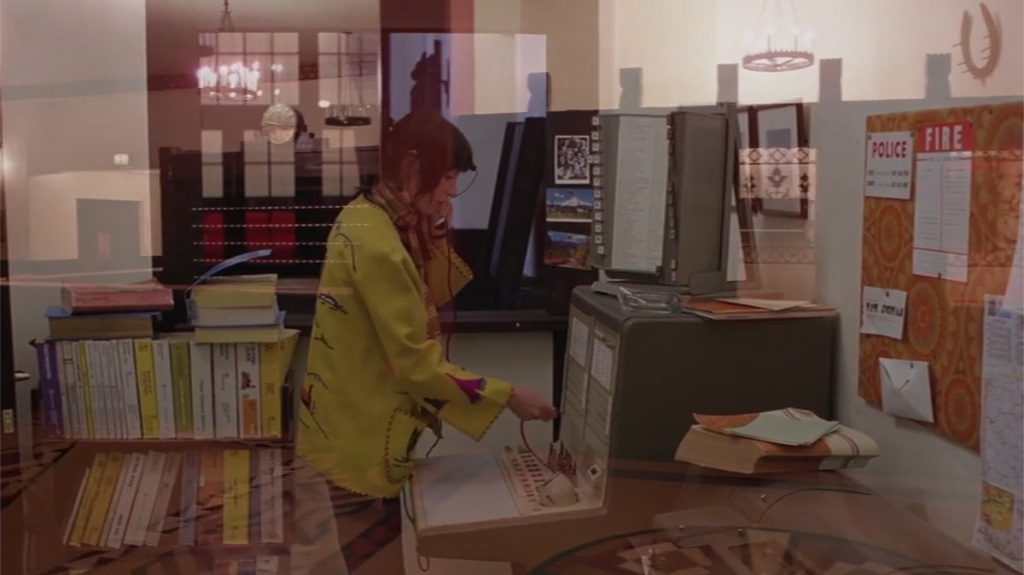

And by the way, this vanishing table and chair happens at exactly 44:07, which is one of only three times that the film’s time code can perfectly resemble the number of pages in the book: 447. This number first became significant to me when I realized how, at 47:40 Wendy passes between two painting for exactly one second. One is by Tom Thomson, and one I highly suspect to be by Alois Arnegger. If you’ve read my Tower of Fable analysis, you know how two guys name Aarne and Thompson created the Aarne-Thompson Folktale Motif Index, a series of thousands of codes (AT codes) that attempt to categorize all the fables in human history. And you know that dozens of relevant folktale numbers appear in the Overlook storeroom, or, as Hallorann seems to call it, the story room.

There is, in fact, no AT code for 447. The nearest code that does exist is 449, and this appears, in isolation, on the licence plate of a 1973 Mercury Marquis Colony Park that the gang pass from 23:31 to 23:39. This is for the fable The Queen’s Dog, and likely reflects Jack’s transformation into the hotel’s Big Bad Wolf. The character Jack is compared to the most in the novel is Bluebeard, the code for which is 312, a jumble of the time code that started this shot (23:31). The mirror action for this 449 going by is Dick coming to the rescue in his snowcat, remember.

So there’s this one 447 moment (44:07) utilizing a vanishing object to shrink The Shining down into a nugget: Jack loses his mind, therefore Wendy and Danny will ride a snowcat to safety.

The other two such “447” moments, 4:47 and 40:47, feature the two breakfasts where Danny is watching Roadrunner. In the first instance, Danny is finishing reacting to Wendy saying it takes time to make new friends. He says, “Yeah, I guess so” and the sound of the cartoon is of a train whistle blowing.

In fact, I was just able to confirm, thanks to the cartoon being online, that the first part of the cartoon that Danny is watching is 12 seconds ahead of every accompanying moment. So, we enter the Boulder apartment at 4:17 (a number associated to the concept of “home” in the film), and the cartoon is at 4:29 of its runtime. In the novel, 429 is the page that Danny defeats Jack, for reasons having to do with several of the major themes I’ve explored throughout this site.

So the cartoon plays consistently with the accompanying Shining action right up until 4:54 of the film, which is 5:06 from the cartoon (37 seconds of cartoon). At that point the cartoon jumps ahead to 5:15, or 21 seconds ahead of the film’s time code. It’s consistent again until 5:03 of the film (9 seconds), at which point it jumps again, from 21 seconds ahead (5:24) to 23 seconds ahead (5:26), and plays for 2 seconds, then jumps again to 32 seconds ahead of the film (5:06-film/5:38-cartoon), and fades out at 5:44 of the cartoon and 5:12 of the movie. So that’s:

- 12 seconds ahead (for 37 seconds)

- 21 seconds ahead (for 9 seconds)

- 23 seconds (for 2 seconds)

- 32 seconds (for 6 seconds)

That’s a combined 54 seconds, which would seem to be a mash-up of 37 and 17, the two evil rooms from book and film. Split by the appearance of Tony at 4:54. As for the 17 seconds being broken into a 9-2-6, you can jumble those digits to get 269, which is 4:29 in seconds. So the 37-second chunk would start at 4:29 of the cartoon, and the 17-second chunk would be a 4:29 jumble. Two ways of spelling Danny’s escape success.

This also means that the 4:47 point of the cartoon occurs at 4:35 of The Shining, where Danny says “Yeah, I guess so” to Wendy insisting that the Overlook will be a lot of fun. A line he’ll repeat at exactly 4:47. And during the corresponding parts of the cartoon, the coyote will be chasing the roadrunner up and down a series of Seussian mountain-side train bridges, resulting in him running into a tunnel where he encounters a train that chases him back out. The mirror action for this part of the film is Jack stomping around in the fresh snow, looking for wherever Danny’s escaped to, while the boy makes the final four left turns that will get him out of the maze. At exactly 4:47 forward Danny’s eyes are fixed on the cartoon (showing the coyote get chased by the train), while a spooky Jack is looming in his cranium, defeated, and crazy. And recall that the next film seen playing on this TV is Carson City, which is all about building a railroad through the mountains – the scene from that film in this film being of one such mountain-tunnel-blasting sequence.

At 4:47 into the cartoon (4:35 of the film), Wendy is holding open the middle of Catcher in the Rye, which might mean she’s reading the exact middle page, page 117. Which is the part of the novel where Holden Caulfield fantasizes about running away to go live in a cabin in the woods (to get away from all the phonies – classic Holden!). But yes, 117 also happens to be our Tower of Babel number, another major subtextual story within the film.

But, putting aside the complexity, the 4:47 moment is about how all these stories are informing our story. And it also says a fair bit about how our story works. Numbers are important, time codes are important, other narratives are important. And you start to wonder, where does the coyote stop and Jack begin? Is Wendy relating to Holden’s desire to get lost in the woods when Danny interrupts her? If Danny is a Christ figure, what does he think about the Tower of Babel? Actually, that reminds me: thanks to the incredible analysis of Valerio Sbravatti, we know that the editors on the film manipulated the Penderecki songs that play over much of the film, so that they start and stop midway through the various compositions used. That’s happening on the other side of the film here, as Danny and Jack chase around, so the Roadrunner manipulations are not unique.

The 40:47 moment features the cartoon playing in the backwards action from 99:30 to 101:17 of the proper film (107 seconds). From 99:30-100:27 (or 41:03-42:00 of the first half) it’s just the opening theme to the show (57 seconds), which doesn’t appear before the cartoon as a stand alone short film, which is the version that gives us these relevant time codes, so I don’t think we’re meant to count it. The cartoon starts at the 1:12 mark and plays to 1:21 (100:28-100:37 – technically 10 full seconds (or 40:53-41:02)), then it jumps 1:12 ahead to 2:33 and plays to 3:12 (100:38-101:17 – technically 40 full seconds (or 40:13-40:52).

So, this second breakfast is full of twinning items, as we’ve covered, but it’s also cool that the gaps in the episode would be equally twinny. Everything starts 1:12 into the official cartoon, and then jumps 1:12 ahead during the one break – also, recall that the first cartoon was for 54 seconds, and this one’s almost perfectly twice as long (107 seconds). The 40:47 moment is 2:38 (Hallorann’s death number) into the cartoon, at which point a giant boulder slams down on Coyote, after he tried to drop it in Roadrunner’s path (which is absurd). So this “story moment” is about how Danny will evade a Jack who will thwart himself by taking on a superior adversary (and Danny’s method of dispatch (the lessons and escapes) is fairly absurd). And if you haven’t read about how 238 relates to the moon, that’s the average distance between the earth and the moon, 238,000 miles, and the Apollo 11 crew took the CSM-107 to get to the moon, and that’s the number on the door behind Wendy’s head when she’s seeing the blowjob bear in the Conquest Well. Also, the cartoon is broken into sections of 57, 10, and 40, right? Well, the first time anything went into space was Sputnik, which launched…on October 4th, 1957.

Also, the news lady, Bertha Lynn, is saying in this second how “24-year-old” Susan Robertson is lost in the mountains. Is 24 a callback to the 42 on Danny’s shoulder in the first breakfast? Actually, when Dick dies, Danny is safe in his comfy bed in Boulder, is that why Kubrick picked an episode where a boulder drops on Coyote…? Isn’t it in Boulder that the escape key appears, allowing Danny to…escape? In fact, the song that plays when Dick goes down is about the part of the Jesus myth where the boulder rolls away and reveals the empty tomb.

Generally speaking, there’s a slew of numbers of major significance in the Roadrunner time codes.

- 1:17 in the cartoon is 40:57/1:40:33. Here Bertha Lynn says “predicted snowstorm” in a sentence about calling off the search for the missing Aspen woman.

- 1:19 (40:55/1:40:35) relates to Danny’s firetruck/Emergency fandom, and Lynn is saying “call off the search”.

- 2:34-2:42 relates to the Avenue of the Dead theory, since these time codes account for the majority of the rooms signified to the various characters. This overlays 1:40:39-1:40:47. At 1:40:39 Wendy is saying she’ll be back in “just about 5 minutes” (2:34), then “I’m gonna lock the door behind me” occurs atop 1:40:42-1:40:43 (2:37-2:38). In the cartoon this is all build up, waiting for the Roadrunner to come and get smushed by the boulder (Coyote pulls the rope at 2:38, Dick’s trap number).

- The one really cool thing there is how 1:40:39 syncs with 2:34. My theory is that the Grady daughters live in room 234, and 1439 (1:40:39) is the number that appears beside Jack the entire time he’s in the storeroom. Recall that that’s the second of the film (23:59) where he gives his “word” that he’ll kill his family, sealing his fate as a corpse ghost of the hotel’s.

- In addition to that, 4:47 is itself “just about 5 minutes”. But exactly 5 minutes after she says that, Danny gets a REDRUM vision interrupting his bloodfall vision. In precisely the same manner as the twins interrupted his earlier vision.

- Also, I believe the hotel wanted to absorb Danny into room 242, so it’s neat that that second of the cartoon would pair with time code 1:40:47, which is like another imperfect 447. Recall that 4:17 seems to express a concept of “home” for Danny, so the hotel wanted to absorb him into 242, his new home.

- As for the opposite of 2:34-2:42, this is for 40:43-40:51, which tracks with the majority of the Susan Robertson story.

- 2:34 (40:51) = “She disappeared while on a hunting trip…” (the real Grady daughters are perhaps symbolized by a couple of hunting dog portraits)

- 2:36 (40:49) = “…missing 10 days…” (Wendy’s story takes place over 10 days)

- 2:37 (40:48) = “…Susan Robertson has been…” (Ullman’s secretary is named “Susie”)

- 2:38 (40:47) = “…24-year-old…” (Danny wore a “42” shirt at first breakfast)

- 2:42 (40:43) = “And the search continues…”

- 3:12 (40:13) = The cut from the aerial shot of the maze to Danny and Wendy marching up the centre of the path. Since 312 is the Bluebeard code, I thought it was worth pointing this out. Novel Danny thinks of the folktale thanks to room 217, and the aerial maze shows us that it has a 23×7 design in it. Also, the action in the cartoon at this point is that Coyote is digging a hole, while a book lays open whose title is HOW TO BUILD A BURMESE TIGER TRAP. Jack will indeed trap the tiger in Danny’s life, but this moment shows us where Danny will trap Jack.

- Also, Danny trikes at room 231, Jack’s death room, from 41:32-41:39, at which point in the opening lyrics to the Roadrunner Show (21-28 seconds into the sequence) are “Roadrunner/That Coyote’s after you/Roadrunner/If he catches you, you’re through”

- I also want to point out how (from 40:38-40:42) Bertha Lynn says that someone named “Rutherford” was “serving a life sentence for his conviction in a 1968 shooting”. This plays over 2:43-2:47 of the cartoon, in which Roadrunner appears and sticks his tongue out at the boulder-smushed Coyote. I don’t believe I’ve discovered a certified connection in any of the other art objects to a “Rutherford”, but after doing a quick search, I found that there’s a US President by that name (Danny’s escape in the novel relates to presidents, and the novel also references the “Hayes office” on page 157), and a guy named Lewis Morris Rutherford who was famous for taking the first telescopic photos of the moon (Danny’s escape in the film relates to the moon). I mention him especially because there’s a bunch of “Louis” and “Maurice” references in the hotel lobby. But that connection to the moon might explain the “1968 shooting” bit. Kubrick shot 2001: A Space Odyssey in that year, so perhaps Kubrick was making a subtle self-reference there.

As for jumbles of 447: I talked about 47:40 being the point Wendy passes between the Arnegger-Thompson paintings, but what’s really cool is that the one-third mark of the film is 47:18, but that’s including the 14 seconds of opening Warner Bros. logo. So the one-third mark of the visual film is actually a sort of secret 47:04. What’s neat about this moment is that the (likely) Arnegger painting is obscured by the directory on top of the radio, and the Thompson is obscured by Wendy’s face (it appears in flashes as she wobbles), and the Thompson will appear in the mirrorform behind Jack as he paces back from killing the radio, but it’s not visible at this point. What is visible are the postcards (one of which is by Francis Kies) that speak to the start of the story, and of course the EYE SCREAM note. The one painting that is visible behind the radio (of a horse/dog on a snowy hill) I suspect to be by Rick de Grandmaison (son of Nick de Grandmaison, whose work definitely appears in the film), and that’s a French name meaning “Big House”. This is a story about a big house, let’s face it.

The official 47:04 is Jack typing away on SATURDAY morning (beneath a painting of a (likely) Br’er Rabbit) while opposite side Jack is entering Ullman’s to kill the radio, passing the “winter” and “spring” photos of Mt. Hood by Mike Roberts and Francis Kies, and The Great Earth Mother by Copper Thunderbird (Norval Morrisseau), with the Be’ena Za’a mural in there for good measure. All in all, there’s a lot going on here about the cycles of nature, as interpreted by folks indigenous to the Americas.

7:44 is the start of Ullman saying “For some people, solitude and isolation can, of itself, become a problem.” It’s also the first second of the backwards Famine Ball, with the skeleton butler standing by the model maze. This is a story about the four horsemen of the apocalypse. But maybe this is to say that it’s about famine especially, and I think that’s fair. While conquest, war and death are all certainly major subtexts, what the Torrances go through more than anything is their isolation. A social famine.

70:44 is a second before the very middle of the movie, at which point we have The Door beside Hallorann on both sides of the film for the combined 3 seconds (70:44-70:46) it takes for the other one to pass away on the other side. That’s one of the most significant alternate stories within this story, since it seems to imply we should study the film mirrorformally.

There are a few other books here that appear in Boulder, including one that contains the word “Europe” in the title, and one that appears above the doctor’s head that can’t be deciphered (the print’s too small in both rooms). I imagine that if we ever get these, we’ll get a lot more insight, but my guess is that the Europe one would allude to WWII, and other ones are possibly classic works of literature referenced in King’s novel, like Treasure Island or Grimm’s Fairy Tales or Alice in Wonderland or Welcome to Hard Times or McTeague. Honestly, though, who knows? As for the photo of Azizi Johari (if that’s who she is), we don’t know the name of this piece, but we know she’s the model in the piece on the opposite side, and that’s one’s called Supernatural Dream, a very Shining kind of concept. Johari is perhaps most otherwise famous for being a Playboy Playmate of the month (June 1975) and probably most seen as the Ring Girl in the first Rocky movie. The Shining contains a few Rocky connections (like how Larry Durkin is played by Tony Burton, who played Apollo Creed’s trainer in that film), but also, this story takes place almost exclusively in the Rocky Mountains.